HN723: ‘It’s like Legos’: Developing a Network Automation Framework

Right now, we have the building blocks for network automation, but we don’t have end-to-end designs or complete systems. It’s like having a bunch of Legos but no instructions for how to build your spaceship. Ryan Shaw, David Sinn, and their colleagues in the Network Automation Forum are tackling this problem. Their goal is to... Read more »Ansible Subelements Lookup Example

When you're working with Ansible, you often come across situations where you need to deal with lists inside of lists. Imagine you have a bunch of servers, and each server has its own set of services to manage.

The subelements lookup plugin is designed to iterate over a list of dictionaries and a specified sub-list within each dictionary. Instead of writing complicated code to dig into each layer, subelements lets you glide through the outer list and then dive into the inner list easily.

What we will cover?

- Subelements syntax

- Subelements example

- What are item.0 and item.1?

- Subelements example with NetBox

Subelements Syntax

To use subelements in your playbook, you write a loop that tells Ansible what main list to look at and which sublist to go through. Here’s what a simple line of code looks like.

loop: "{{ query('subelements', your_main_list, 'your_sublist_key') }}"your_main_list is where you have all your main items (like servers), and your_sublist_key is the name of the sublist inside each main item (like tasks for each server). Ansible will then loop through each main item and its sub-items in turn.

Ansible Subelements Example

Suppose you have the following data structure defined in your playbook.

Continue readingnetlab on Packet Pushers

A few weeks ago, Ethan Banks invited me to chat about netlab, and we had great fun discussing its intricacies for almost an hour. I also managed to win the Buzzword Bingo describing netlab as

Intent-based infrastructure-as-code digital twins lifecycle management system

The podcast was published a few days ago; listen to it on the PacketPushers website or YouTube.

netlab on Packet Pushers

A few weeks ago, Ethan Banks invited me to chat about netlab, and we had great fun discussing its intricacies for almost an hour. I also managed to win the Buzzword Bingo describing netlab as

Intent-based infrastructure-as-code digital twins lifecycle management system

The podcast was published a few days ago; listen to it on the PacketPushers website or YouTube.

Electrics and plumbing

Unless you plan to live by candle light and bathe in the canal you are going to need electrics and hot water. The two main players when it comes to boat electrics are Victron and Mastervolt, I went for victron as their whole eco-system seems a lot more advanced and customisable (are a lot more guides, examples and advise readily available online). In terms of hot water and heating a calorifier is the only real sensible option, for the diesel heater I chose Webasto over Eberspacher as I liked how they how they have incorporated the use of Heatmiser thermostat controllers.

KU049: Security Frameworks, Tools, and Strategies for Kubernetes

Kubernetes is designed to be highly scalable and highly dynamic… a perfect habitat for cryptominers to terminal shell into and then exploit your workload’s resources to the max. And that’s just one example of security threats Kubernetes users need to prepare against. Nigel Douglas from Sysdig joins Michael Levan and Kristina Devochko to give you... Read more »Defining AI’s Role in Network Management

AI isn't going to put human network managers out of work. It will, however, help managers become more insightful and efficient.polyfill.io now available on cdnjs: reduce your supply chain risk

Polyfill.io is a popular JavaScript library that nullifies differences across old browser versions. These differences often take up substantial development time.

It does this by adding support for modern functions (via polyfilling), ultimately letting developers work against a uniform environment simplifying development. The tool is historically loaded by linking to the endpoint provided under the domain polyfill.io.

In the interest of providing developers with additional options to use polyfill, today we are launching an alternative endpoint under cdnjs. You can replace links to polyfill.io “as is” with our new endpoint. You will then rely on the same service and reputation that cdnjs has built over the years for your polyfill needs.

Our interest in creating an alternative endpoint was also sparked by some concerns raised by the community, and main contributors, following the transition of the domain polyfill.io to a new provider (Funnull).

The concerns are that any website embedding a link to the original polyfill.io domain, will now be relying on Funnull to maintain and secure the underlying project to avoid the risk of a supply chain attack. Such an attack would occur if the underlying third party is compromised or Continue reading

Zaraz launches new pricing

In July, 2023, we announced that Zaraz was transitioning out of beta and becoming available to all Cloudflare users. Zaraz helps users manage and optimize the ever-growing number of third-party tools on their websites — analytics, marketing pixels, chatbots, and more — without compromising on speed, privacy, or security. Soon after the announcement went online, we received feedback from users who were concerned about the new pricing system. We discovered that in some scenarios the proposed pricing could cause high charges, which was not the intention, and so we promised to look into it. Since then, we have iterated over different pricing options, talked with customers of different sizes, and finally reached a new pricing system that we believe is affordable, predictable, and simple. The new pricing for Zaraz will take effect on April 15, 2024, and is described below.

Introducing Zaraz Events

One of the biggest changes we made was changing the metric we used for pricing Zaraz. One Zaraz Event is an event you’re sending to Zaraz, whether that’s a pageview, a zaraz.track event, or similar. You can easily see the total number of Zaraz Events you’re currently using under the Monitoring section in the Cloudflare Zaraz Continue reading

Remediating new DNSSEC resource exhaustion vulnerabilities

Cloudflare has been part of a multivendor, industry-wide effort to mitigate two critical DNSSEC vulnerabilities. These vulnerabilities exposed significant risks to critical infrastructures that provide DNS resolution services. Cloudflare provides DNS resolution for anyone to use for free with our public resolver 1.1.1.1 service. Mitigations for Cloudflare’s public resolver 1.1.1.1 service were applied before these vulnerabilities were disclosed publicly. Internal resolvers using unbound (open source software) were upgraded promptly after a new software version fixing these vulnerabilities was released.

All Cloudflare DNS infrastructure was protected from both of these vulnerabilities before they were disclosed and is safe today. These vulnerabilities do not affect our Authoritative DNS or DNS firewall products.

All major DNS software vendors have released new versions of their software. All other major DNS resolver providers have also applied appropriate mitigations. Please update your DNS resolver software immediately, if you haven’t done so already.

Background

Domain name system (DNS) security extensions, commonly known as DNSSEC, are extensions to the DNS protocol that add authentication and integrity capabilities. DNSSEC uses cryptographic keys and signatures that allow DNS responses to be validated as authentic. DNSSEC protocol specifications have certain requirements that prioritize availability at Continue reading

How to Export Large Traffic Logs from Palo Alto Firewall?

Recently, I faced a unique challenge, I needed to export a massive amount of traffic logs from a Palo Alto Firewall for analysis. Initially, I thought it would be straightforward, log into the GUI, apply the necessary traffic log filter, and export the logs as a CSV file. Easy peasy, right? Well, not exactly. I quickly ran into a roadblock that made me rethink my approach.

In this blog post, I'll share the hurdles I encountered and how I managed to find a workaround to export the logs and analyze them using Python Pandas.

The Problem

By default, Palo Alto only exports 65535 rows in the CSV file, which is not nearly enough. If you have a large network, that amount might only cover a few minutes of logs. Even if you change the value, the maximum it can support is 1048576, which might cover maybe an hour's worth of logs. But for my use case, I needed at least a month of logs. I couldn't get what I wanted from the built-in report options, so I was scratching my head. I then tried to export the logs via SCP on the CLI, but again encountered the same maximum row Continue reading

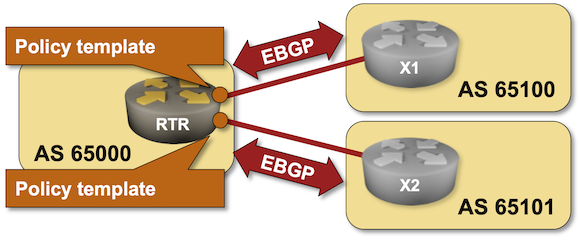

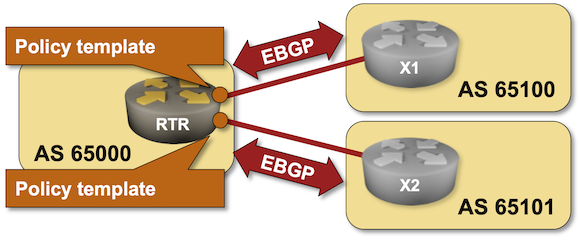

BGP Labs: Policy Templates

One of the previous BGP labs explained how you can use session templates to configure common TCP or BGP session parameters. Some BGP implementations have another templating mechanism: policy templates that you can use to apply consistent routing policy parameters to an EBGP neighbor. You can practice them in the next BGP lab exercise.

BGP Labs: Policy Templates

One of the previous BGP labs explained how you can use session templates to configure common TCP or BGP session parameters. Some BGP implementations have another templating mechanism: policy templates that you can use to apply consistent routing policy parameters to an EBGP neighbor. You can practice them in the next BGP lab exercise.

A Perfect Cyber Storm is Leading to Burnout

Meeting the cybersecurity demands of modern enterprises is incredibly stressful, causing burnout and leading many to contemplate leaving the field. Here’s how to address the problem.Unlocking new use cases with 17 new models in Workers AI, including new LLMs, image generation models, and more

On February 6th, 2024 we announced eight new models that we added to our catalog for text generation, classification, and code generation use cases. Today, we’re back with seventeen (17!) more models, focused on enabling new types of tasks and use cases with Workers AI. Our catalog is now nearing almost 40 models, so we also decided to introduce a revamp of our developer documentation that enables users to easily search and discover new models.

The new models are listed below, and the full Workers AI catalog can be found on our new developer documentation.

Text generation

- @cf/deepseek-ai/deepseek-math-7b-instruct

- @cf/openchat/openchat-3.5-0106

- @cf/microsoft/phi-2

- @cf/tinyllama/tinyllama-1.1b-chat-v1.0

- @cf/thebloke/discolm-german-7b-v1-awq

- @cf/qwen/qwen1.5-0.5b-chat

- @cf/qwen/qwen1.5-1.8b-chat

- @cf/qwen/qwen1.5-7b-chat-awq

- @cf/qwen/qwen1.5-14b-chat-awq

- @cf/tiiuae/falcon-7b-instruct

- @cf/defog/sqlcoder-7b-2

Summarization

- @cf/facebook/bart-large-cnn

Text-to-image

- @cf/lykon/dreamshaper-8-lcm

- @cf/runwayml/stable-diffusion-v1-5-inpainting

- @cf/runwayml/stable-diffusion-v1-5-img2img

- @cf/bytedance/stable-diffusion-xl-lightning

Image-to-text

- @cf/unum/uform-gen2-qwen-500m

New language models, fine-tunes, and quantizations

Today’s catalog update includes a number of new language models so that developers can pick and choose the best LLMs for their use cases. Although most LLMs can be generalized to work in any instance, there are many benefits to choosing models that are tailored for a specific use case. We are excited to bring you some new large language models (LLMs), small language models (SLMs), Continue reading

Another Ethernet VPN (EVPN) Introduction

Ethernet VPN (EVPN) Introduction

Instead of being a protocol, EVPN is a solution that utilizes the Multi-Protocol Border Gateway Protocol (MP-BGP) for its control plane in an overlay network. Besides, EVPN employs Virtual extensible Local Area Network (VXLAN) encapsulation for the data plane of the overlay network.

EVPN Control Plane: MP-BGP AFI: L2VPN, SAFI: EVPN

Multi-Protocol BGP (MP-BGP) is an extension of BGP-4 that allows BGP speakers to encode Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI) of various address types, including IPv4/6, VPNv4, and MAC addresses, into BGP Update messages.

The MP_REACH_NLRI path attribute (PA) carried within MP-BGP update messages includes Address Family Identifier (AFI) and Subsequent Address Family Identifier (SAFI) attributes. The combination of AFI and SAFI determines the semantics of the carried Network Layer Reachability Information (NLRI). For example, AFI-25 (L2VPN) with SAFI-70 (EVPN) defines an MP-BGP-based L2VPN solution, which extends a broadcast domain in a multipoint manner over a routed IPv4 infrastructure using an Ethernet VPN (EVPN) solution.

BGP EVPN Route Types (BGP RT) carried in BGP update messages describe the advertised EVPN NLRIs (Network Layer Reachability Information) type. Besides publishing IP Prefix information with IP Prefix Route (EVPN RT 5), BGP EVPN uses MAC Advertisement Route Continue reading

D2C235: Building Modern Apps In GovCloud

Chances are, you’ve probably only heard of GovCloud because at the bottom of new feature releases from the Big 3 there’s usually an asterisk that says “not yet available in GovCloud.” So what is GovCloud? And why does it not get the newest shiny thing as fast as the rest of us? Chris Wahl has... Read more »Open sourcing Pingora: our Rust framework for building programmable network services

Today, we are proud to open source Pingora, the Rust framework we have been using to build services that power a significant portion of the traffic on Cloudflare. Pingora is released under the Apache License version 2.0.

As mentioned in our previous blog post, Pingora is a Rust async multithreaded framework that assists us in constructing HTTP proxy services. Since our last blog post, Pingora has handled nearly a quadrillion Internet requests across our global network.

We are open sourcing Pingora to help build a better and more secure Internet beyond our own infrastructure. We want to provide tools, ideas, and inspiration to our customers, users, and others to build their own Internet infrastructure using a memory safe framework. Having such a framework is especially crucial given the increasing awareness of the importance of memory safety across the industry and the US government. Under this common goal, we are collaborating with the Internet Security Research Group (ISRG) Prossimo project to help advance the adoption of Pingora in the Internet’s most critical infrastructure.

In our previous blog post, we discussed why and how we built Pingora. In this one, we will talk about why and how you might Continue reading

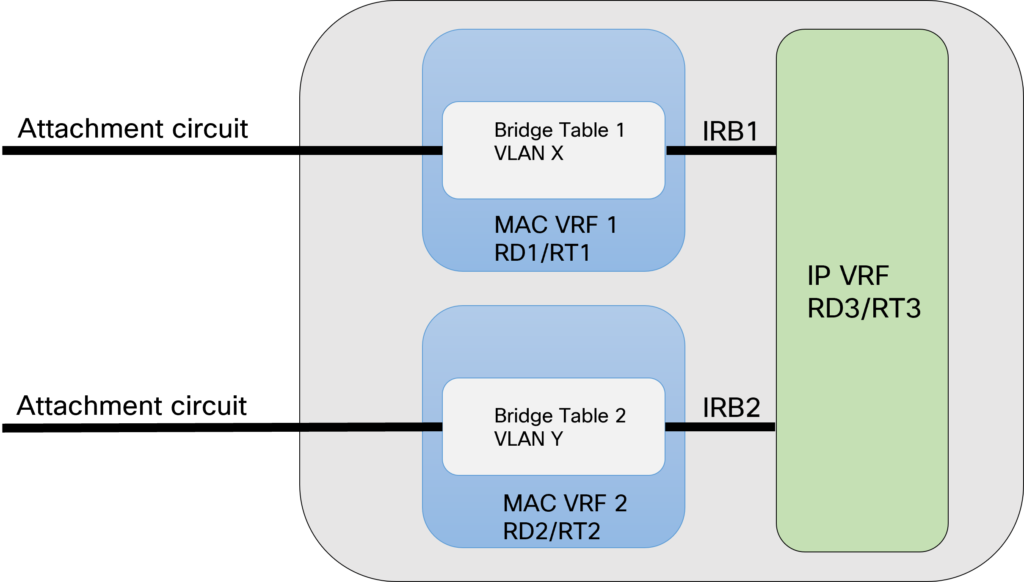

EVPN Terminology

Reading RFCs is a great source of information for understanding all the details of a protocol. Often they do require the reader to be quite technical and the terminology can be confusing if you aren’t used to the type of language and writing style used in RFCs. In this post, I go through some of the most important terminology in EVPN and VXLAN to help you build your understanding of the different forwarding constructs and how they interact.

The picture below shows some of the most important terminology in EVPN:

Let’s go through the terms used in the diagram and some additional ones:

- Attachment circuit – An interface that is associated with a bridge table. The AC that the packet arrived on is determined by examining the port, and optionally VLAN tag.

- Broadcast Domain – The Broadcast domain consists of all devices and hosts that would receive a broadcast frame when sent in that domain (assuming no ARP optimization features used). This is normally a VLAN, and it normally maps to one subnet. From a VXLAN perspective, it would be a L2 VNI. An EVI may contain one or more BDs depending on service model.

- Bridge Table – Bridge Table Continue reading

DHCP Relaying on a Linux Host

Markku Leiniö sent me an interesting observation after writing a series of DHCP-relaying-related blog posts:

I was first using VyOS, but it uses the ISC DHCP relay, and that software relays unicast packets. The DHCP procedures eventually worked fine, but getting sensible outputs and explanations was a nightmare.

I quickly reproduced the behavior, but it took me almost half a year to turn it into a blog post. Engaging in a round of yak shaving (I wanted to implement DHCP in netlab first) didn’t exactly help, either.